Area of Focus

Energy

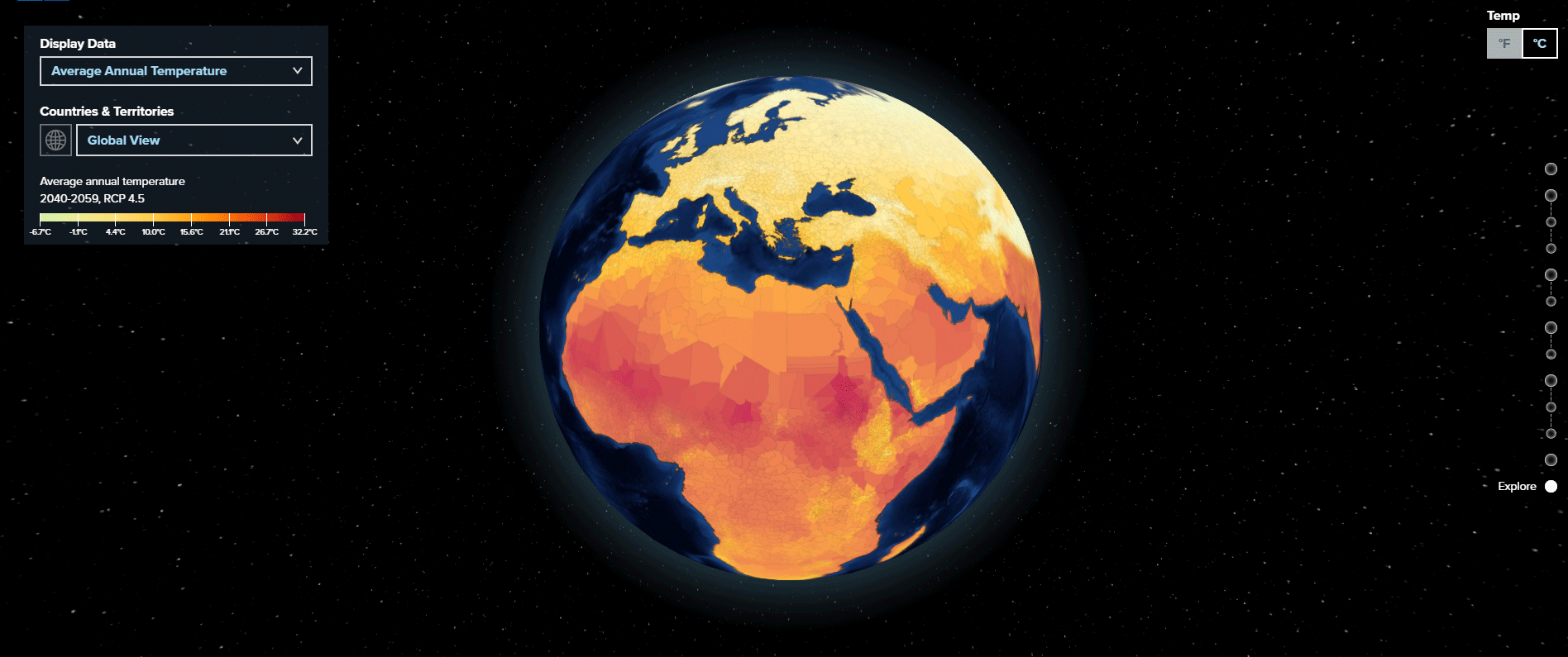

Energy systems as currently designed are poorly prepared for future climatic changes. Rising temperatures, increased competition for water supply, and elevated storm surge risk will affect the cost and reliability of energy supply.