A changing climate brings higher temperatures and increased humidity to many parts of the U.S., limiting how often football players are able to be on the field, both practicing their sport and competing in games. Wearing more equipment means the human body must work harder to maintain safe core temperature. The Korey Stringer Institute, named after a pro-bowl tackle for the Minnesota Vikings who died in 2001 after collapsing from a morning practice in 91-degree heat, has pioneered much of the research around heat stress and sport. Already, athletic officials are starting to take action, like mandating the “helmets only” summer practices to allow players to adjust to the heat before they suit up in full pads.

Over the past decade, many U.S. states have adopted rules requiring football teams to monitor weather conditions on the practice and playing field. Officials use a composite temperature metric that takes into account air temperature and humidity, in addition to wind speed, cloud cover, and the angle of the sun on the human body. This “wet bulb globe temperature” reading tells the athletic trainer or coach what the weather feels like for a player engaged in strenuous exercise. If it passes certain cutoff points, practices must be shortened, equipment must be shed, or athletes must be given more frequent rest and water breaks. A high enough reading will cancel all outdoor activity until conditions improve.

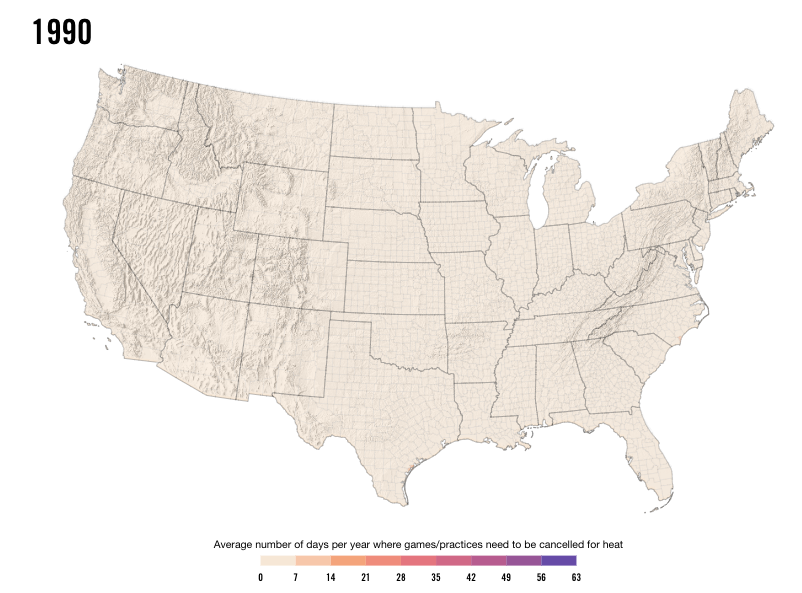

Three decades ago, these conditions were rare.

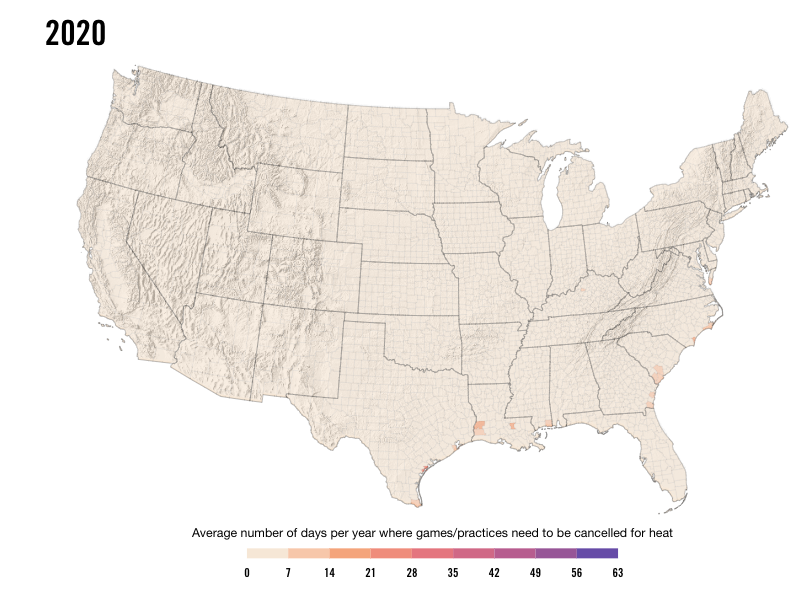

Today, changes in the climate increasingly expose players to higher temperatures and dangerous levels of humidity, crossing recommended safety thresholds. Along the Gulf Coast, counties in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi can expect roughly one to two weeks of play-limiting conditions each year. Counties in North Carolina, South Carolina and parts of Georgia are also impacted.

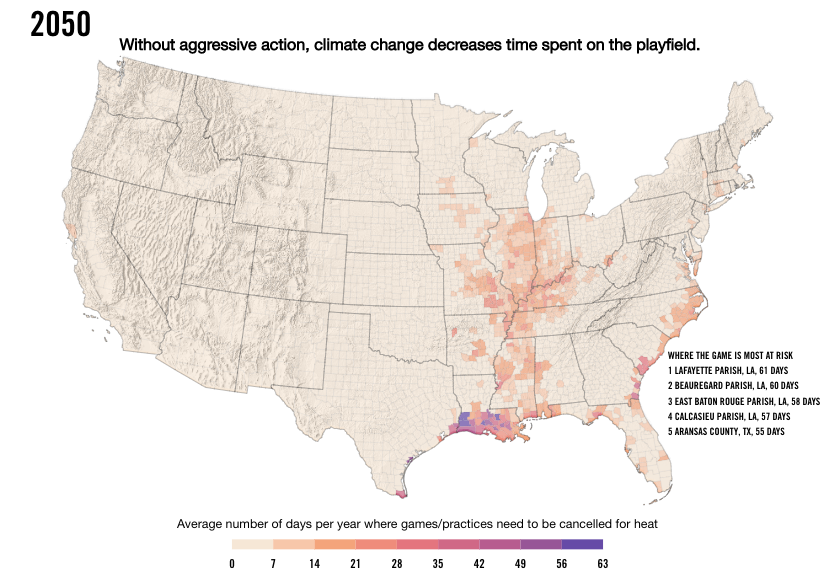

Continuing on a high emissions path means a shrinking football season for the next generation of players. By the 2050s, Louisiana’s East Baton Rouge Parish could expect 34 to 70 fewer days each year suitable for football. In Texas’ Galveston County, projections show 17 to 46 days of these days each year.

Ahead of Climate Week in New York City, Nike partnered with researchers from the Climate Impact Lab to show the connection between climate change and sport. Researchers at Rhodium Group, through its collaboration with the Climate Impact Lab, powered the data and analysis behind an interactive visual essay launched on purpose.nike.com/climate-and-sport. Through the eyes of athletes, our research helps bring to life the connection between a stable climate and athletic performance and the future of our playing field–planet earth. The experience shows rising temperatures putting additional strain on the human body or making it harder for runners to clock a new personal best. We show how climate change could push some of the world’s top competitions toward increasingly hot and exhausting conditions, and potentially decreasing the amount of time spent on the playing field.