New data platform from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Climate Impact Lab provides the first empirical, peer-reviewed evidence that climate impacts will fall disproportionately on the poor.

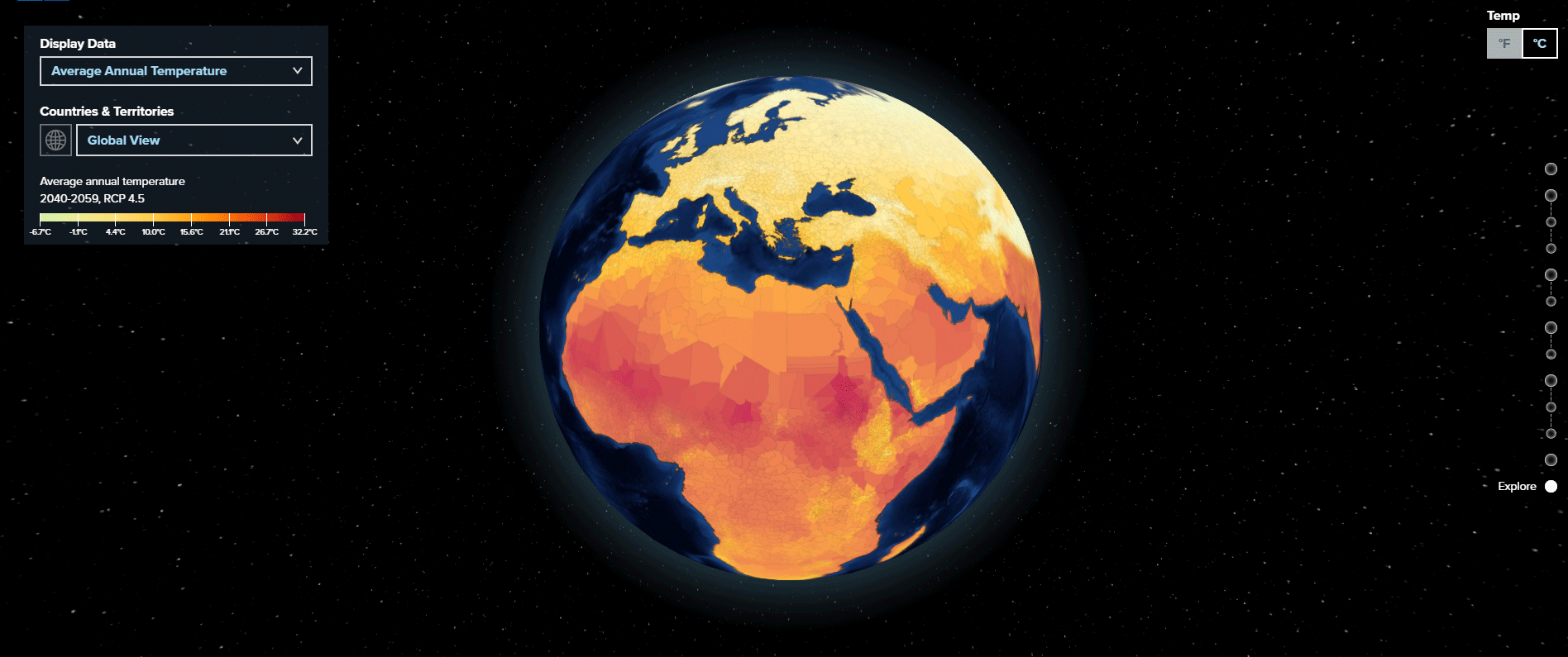

Geographic inequality will shape the coming decades of our warmer future—a reality made starkly obvious by a new data and insights platform, Human Climate Horizons (horizons.hdr.undp.org). The result of joint work of the Climate Impact Lab and the United Nations Development Programme’s Human Development Report Office, the platform quantifies the effects of warmer temperatures on all-cause death rates, energy use, and time spent working for every country and territory, and for cities and regions within those borders. Launched in the lead-up to COP27, the platform provides the first empirical, peer-reviewed evidence that climate impacts will fall disproportionately on the poor, helping to frame the debate over the unequal harms caused by rising global greenhouse gas emissions and highlighting how the choices we make today can shape human development.

With detailed maps and interactive charts, Human Climate Horizons (HCH) makes evident the broader national and global implications of a warmer climate on our health, our power supply, and our ability to earn a livelihood.

Mortality Impacts

Most striking is the research on global mortality, published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, which finds that climate change, like the COVID-19 pandemic, is likely to hit those with the least the hardest. The HCH platform shows the effect of temperature on death rates is going to be important everywhere in the world as we face a warmer climate, but it will look very different in wealthy, hot places that have the means to respond and adapt than in poor, hot places that do not.

The effect is pronounced, even under a scenario that is broadly consistent with the world’s countries meeting their current emissions reduction pledges under the Paris Climate Agreement (RCP 4.5). By midcentury, Faisalabad, Pakistan, could expect annual all-cause death rates to increase by nearly 67 deaths per 100,000 population compared to a future with no climate change. That effect would be almost as deadly as strokes–currently Pakistan’s third leading cause of death. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, experiences similar patterns of warming and extreme heat, but people have more resources, including access to electricity and health care, factors that are reflected in the Lab’s research. By midcentury, Riyadh could expect annual all-cause death rates to increase by 35 deaths per 100,000 population compared to a future with no climate change. Still, 35 deaths per 100,000 is more lethal than Alzheimer’s disease, currently the 7th leading cause of death globally.

As further evidence of this inequality in outcomes, the Climate Impact Lab has quantified the cost of these mortality impacts and the cost of adaptations people undertake to protect themselves (air conditioning, cooling centers). Through this lens, CIL finds that the impact on Pakistan by midcentury under this same scenario is equivalent to 8% of its future GDP. For Saudi Arabia, the impact is equivalent to 2% of future GDP. More cost data can be found on CIL’s Impacts Map.

Zooming out for a global view, the HCH platform shows warming is projected to have a beneficial impact on health in certain cold regions by reducing death rates but, overall, the impact is harmful. Under a high emissions scenario (RCP 8.5), global average death rates are projected to increase by 53 per 100,000 population by the end of the century. A clear rich-versus-poor divide can be seen in the data. In that same scenario, climate change is projected to cause an increase in death rates for 35% of the G20 countries. In comparison, 74% of the least developed countries will see an increase in death rates, relative to a future with no climate change.

Energy Impacts

Additionally, the platform reveals a deep divide between wealthy and poor populations when it comes to energy use, a divide that is likely to persist as the planet warms and cooling technologies like air conditioning remain out of reach for more than half of the global population. The globally comprehensive analysis of energy consumption, published last year in the journal Nature, contradicts previous estimates that suggested hotter temperatures would drive massive increases in energy spending by the end of the century. Most of this prior research focused on analyzing the wealthiest parts of the world, without including evidence from the developing world, where billions of people live in poverty and lack energy access. The HCH platform shows that income plays an essential role in people’s ability to protect themselves from the impacts of warming.

While electricity consumption soars on hot days among the richest 10% of the global population—such as Singapore, which has access to air conditioning—lower-income, hot areas are projected to remain relatively poor through 2100 and therefore lack the means to protect themselves with cooling during increased heat, such as much of sub-Saharan Africa. Middle-income regions, like parts of India, China, Indonesia, and Mexico, are projected to benefit from expanded access to electricity. India, for example, is expected to see a 145% increase in electricity consumption in some scenarios, potentially posing a formidable infrastructure planning challenge.

The data shows that—while there are vastly unequal effects among regions—globally, climate change drives a modest uptick in electricity consumption. However, this increase in electricity use does not lead to an increase in fossil fuel use overall, as declines in the need for these fuels for heating offset the increase in the electricity sector. This is especially the case in rich countries with temperate or cool climates, like Canada. (See “Other fuels use” in the figure below).

Labor Impacts

The platform additionally breaks new ground by quantifying the disruptive effects of a warmer climate on the labor force, a crucial component of the economy. The HCH platform shows how time spent working by individual workers in a range of workplaces–from farms to factories to call centers–will evolve over the course of the century as they face increasing discomfort. Workers are divided into two categories based on their industry: high-risk, weather-exposed jobs and low-risk jobs, each of which responds differently to climate change. Heat especially takes a toll on workers in high-risk sectors, like agriculture and construction. In countries where workers already face extreme heat, like Ghana and Myanmar, these interruptions by midcentury add up to more than 16 hours lost annually for each worker compared to a world with no climate change. For a company with a workforce of 200 full-time employees, that equals 400 days per year less worker time on the job.

One of the key insights from the platform is the crucial role that reducing emissions will play in determining our collective future. The platform’s projections for climate change’s impact on human mortality, energy consumption, and labor all rely on the same data-driven, frontier approach to measuring the effects of warming and reveal similar patterns of vulnerability. Users can compare impacts across time frames and two different emissions pathways: moderate emissions (RCP 4.5), where countries meet the Paris goal of limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius, and high emissions (RCP 8.5), where emissions continue to rise in a worst-case scenario resulting in Earth warming nearly 5 degrees Celsius. Combined, this information makes it possible to map how global action to reduce emissions improves outcomes, especially for the disproportionately impacted poorest regions, making progress toward confronting inequality. Continued global progress towards Paris Agreement targets could reduce, for example, projected global mortality from extreme heat at the end of the century by more than 80%, translating into the possibility of saving millions of lives.

Notably, the Climate Impact Lab uses state-of-the-art statistical methods to produce a full range of estimates for 24,378 distinct regions. These include expert projections for future income and population growth, and simulations from 33 climate models, allowing for an assessment of the range of possible risks surrounding any particular projection. The full range of projections is available for download via the Human Climate Horizons platform, empowering policymakers, researchers, and others to prepare for a more sustainable future.

EXPLORE THE HUMAN CLIMATE HORIZONS PLATFORM HERE

—

The Climate Impact Lab extends its sincere gratitude to King Philanthropies for its financial support on this project.

For more information on the Human Climate Horizons platform, including methodology and FAQs, visit: https://horizons.hdr.undp.org/#/what-is-hch